Toolbox

Looking for something specific? Search by topic or enter a keyword below.

Best Management Practices - Design Guidelines - Funding - Policy Recommendations - Partnerships

Looking for something specific? Search by topic or enter a keyword below.

Best Management Practices - Design Guidelines - Funding - Policy Recommendations - Partnerships

The following section identifies the best practices available today for creek management. While not an exhaustive list, ideas should motivate further research into specifics that meet the goals establish by your project.

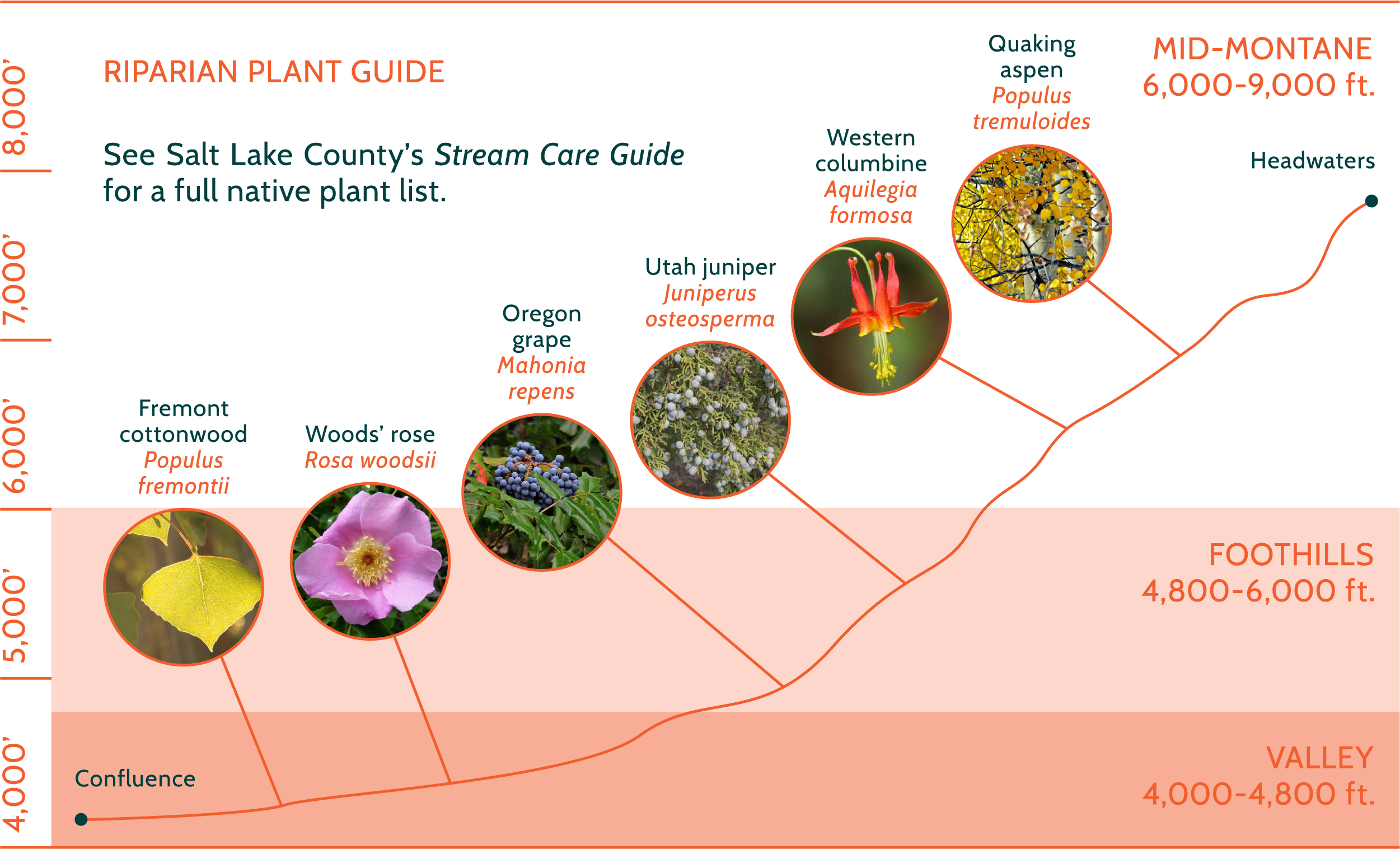

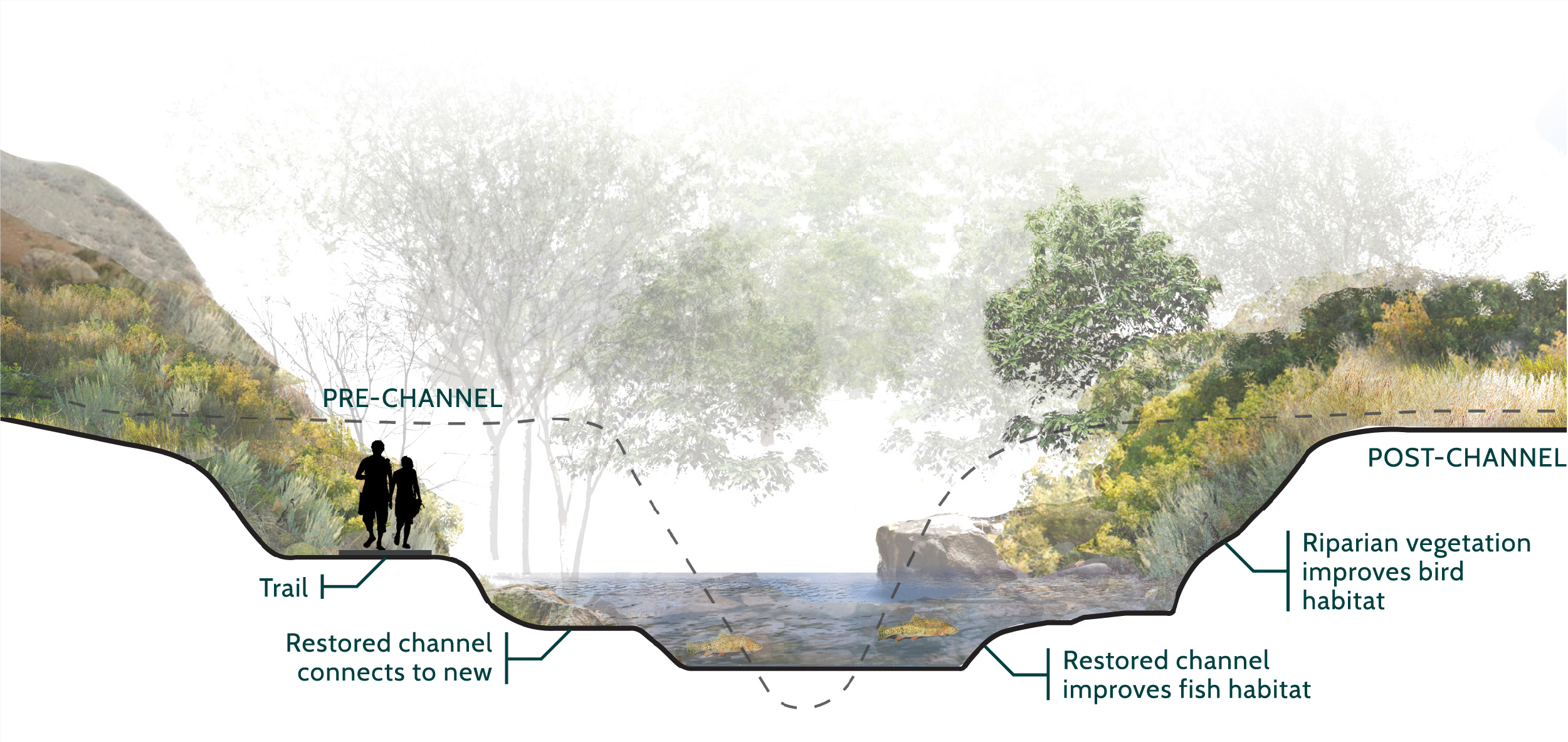

A century of taming and tapping our urban creeks left them in a degraded condition. Industry and development polluted water quality. Creeks were channelized to control flooding. Banks steepened and eroded. Dams and aging infrastructure eliminate fish passage, disjoined wildlife corridors, and reduced access. Stream restoration aims to improve the flows, quality, and health of a waterway and riparian ecosystem. Efforts improve water quality through plantings, bank stabilization, and other green infrastructure. Restoration recreates channel meanders, removes dams, and replaces aging infrastructure. Inclusion or reconnection of a floodplain reduces water velocities to decrease erosion and mitigates flooding.

In the early 20th century, as urbanization gripped the Salt Lake Valley, creeks gave way to concrete and asphalt, bricks and mortar. Waterways were diverted from aboveground channels into stormwater pipes underneath our neighborhoods.

Stream daylighting uncovers a stream previously buried in a pipe or a culvert, bringing it back to the surface and restoring its natural stream channel—or to the most natural state possible. Benefits are abundant, including water and air quality improvements, flood mitigation, habitat creation, economic benefit, expanded recreational opportunities, and more. Other forms of daylighting include architectural and cultural. Architectural daylighting brings a stream to the surface in an engineered channel, characterized by a concrete streambed and banks. Whereas, cultural daylighting celebrates a buried stream through markers or public art to showcase its historic path.

Natural Daylighting

Architectural Daylighting

Cultural Daylighting

Green infrastructure is a cost-effective, resilient tool to manage water in our cities.

Bioswales

Shallow depressions filled with vegetation and rock that contain stormwater and runoff, allowing water to infiltrate into the ground and filter pollutants before reaching waterways. Groundwater is an increasingly important drinking water source with climate change uncertainty. Swales reduce pressure on the stormwater system. Plantings can be chosen for habitat value and highlight those found along our creeks. Swales should be implemented at stormwater outlets along our creeks.

Permeable Paving

Materials that allow stormwater to percolate through and filter into the groundwater, rather than run off the surface. This reduces flash flooding in our creeks by retaining stormwater on-site. Parking lots and impervious surfaces near our creeks should be shifted to permeable paving.

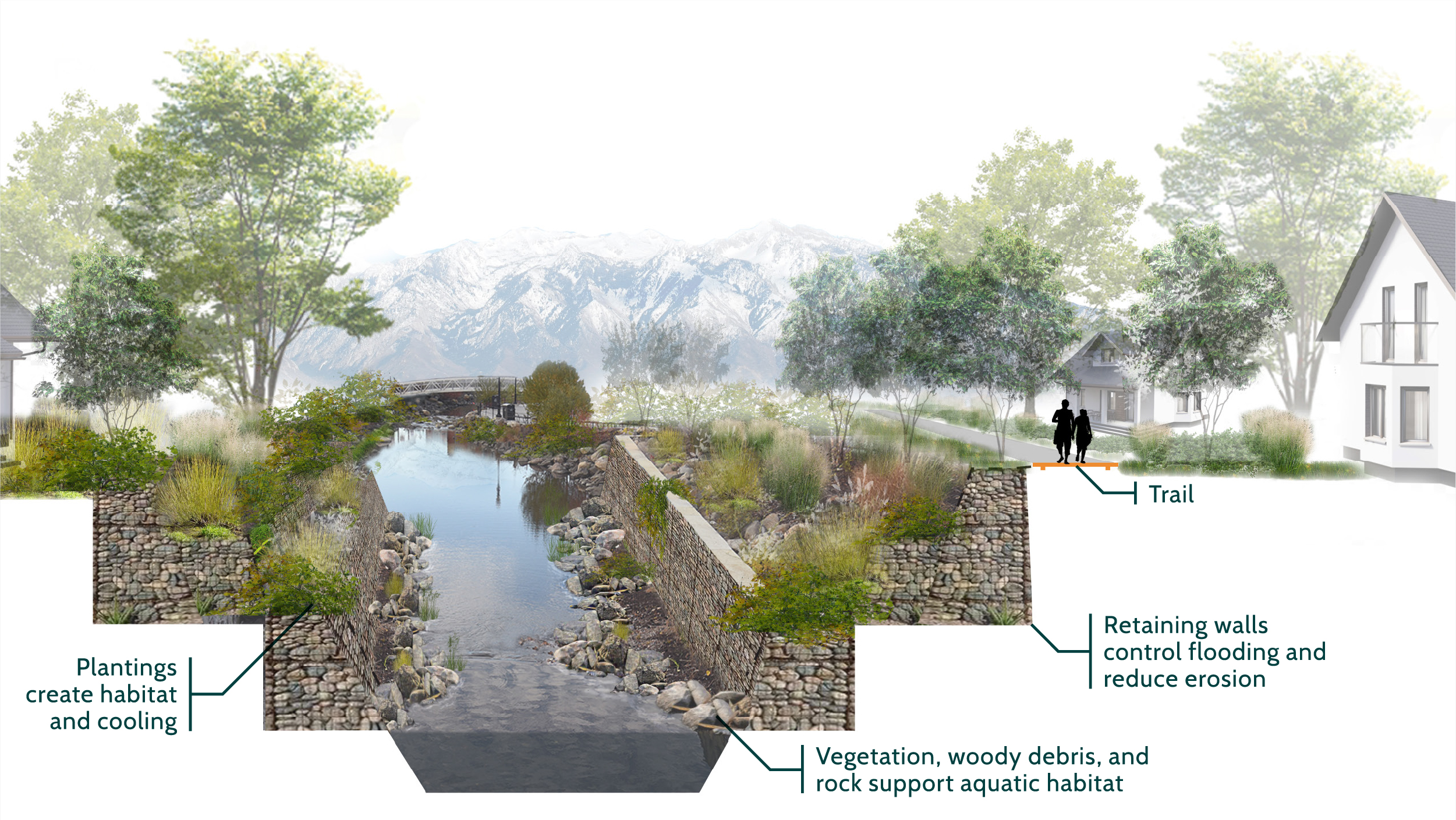

Streambank stabilization reduces erosion and excess sedimentation of our creeks. Efforts should utilize natural methodology, such as bioengineering, to stabilize banks through plantings and root material that hold soil in place. This also provides habitat along the banks and in-stream.

Slopes should be kept at two-to-one. This ensures people can easily escape the channel in dangerous situations. For incised creeks, retaining walls outside the floodplain can reduce elevation. Then, banks stabilized from the wall to the annual high-water level.

If conventional, hardening approaches are deemed necessary, natural rock with desirable plant materials, such as willow and cottonwood, between the rock should be used. This is a safe, aesthetically pleasing approach that provides habitat, when compared to concrete, gabion baskets, or other rip-rap.

Riparian buffers are important to mitigate polluted urban runoff from entering our creeks. Vegetation acts as a barrier, soaking up excess nutrients, especially in locations nearby turf grass in parks, golf courses, and residential lawns. In some areas, creeks are used to create man-made ponds, such as Liberty Pond. Naturalizing pond edges with wetland vegetation improves habitat value, while managing runoff and improving water quality. Buffers are also a simple and effective strategy homeowners can implement to steward our creeks.

Emphasis should be placed on lateral habitat connectivity to create wildlife corridors along our creeks. Infrastructure, such as culverts, buried streams, and dams, should be replaced to improve connectivity. Bridges should be used for stream crossings whenever possible. They provide the lowest impact to hydrology and connectivity and have low maintenance needs. If deemed not possible, open-bottom culverts—with a natural creek bed—can be used for crossing. The width of the culvert should extend out to the full channel width, providing adequate space for the surface water, banks, and adjacent floodplain.

Stream daylighting eliminates buried creeks. Aging infrastructure, such as dams, that is no longer in use should be removed and the creek restored. This improves sediment transport, water quality, and habitat value. Dams that are deemed necessary should be redesigned to limit wildlife disturbance, such as utilizing fish ladders. Operations should also be improved, such as increasing releases at strategic times or during low flow.

Insurance costs can burden low-income residents living in flood hazard areas. Additionally, they are often less able to rebuild or relocate after disasters. Residents that rent properties within hazard areas are not required to buy flood insurance but are at no less risk. The Federal Emergency Management Agency determined that 51 percent of the non-policyholder households in flood hazard areas are low-income [01].

Existing parks, open spaces, and golf courses are excellent areas to recreate floodplains. Floodplain creation should include riparian vegetation restoration, wetland creation, channel remeandering, and streambank stabilization, where feasible. In urban areas, floodplain creation can be more challenging. Surface parking lots and underutilized or vacant parcels provide opportunities to implement these practices.

Sources

[01] Doswell, The Future of Flood Insurance and its Environmental Justice Implications on North Carolina’s Low-Income Communities (2020).

Wetlands are habitats where standing water is at or near the surface for all or a portion of the year. They support critical habitat for aquatic and terrestrial species, improve water quality through nutrient uptake, mitigate flooding by containing and holding high flows, and promote groundwater infiltration. Existing wetlands should always be protected from disturbance. They are also opportunities for targeted restoration to improve habitat value and increase wetland size. In conjunction with floodplain creation, wetlands can add additional habitat value and water quality benefits at existing parks, open spaces, and golf courses or replace underutilized surface parking lots and other parcels along our creeks.

Existing urban forests should be protected and maintained whenever possible. If trees are removed, the urban tree canopy should be replaced two-fold. A diversity of species, age, and size will create a more resilient ecosystem in the face of growing urban pressures and climate change uncertainty. Municipalities should consider ordinances or other policy tools to preserve existing urban forests and encourage planting along our creeks. Holladay implemented a tree preservation ordinance to protect the existing urban forest and require replacement of protected trees that are removed.

In Salt Lake City, the urban forest consists of an estimated 85,000 public trees—63,000 on streets and 22,000 in parks and open spaces [01]. The City’s 1,000 Trees Campaign promises to deliver 1,000 trees to the urban forest every year. It focuses efforts on the City’s west-side where tree canopy is lowest and air quality worst. The effort took on greater importance when hurricane-force winds tore through the Salt Lake Valley in September 2020, knocking down thousands of trees county-wide.

Sources

[01] Salt Lake City, Urban Forestry (2021).

Access to our greenways is currently focused on existing public lands, such as parks, natural areas, and open space. Private property complicates access. However, access has been granted in formal or informal agreements through partnerships with landowners, especially near commercial and civic activation points.

For example, a trail winds along Big Cottonwood Creek through the Cottonwood and Old Mill Corporate Centers. The landowner donated rights-of-way as a means for tenants to access the creek and recreation opportunities. The trail connects the city of Cottonwood Heights, the Old Mill Open Space, and the mouth of the Big Cottonwood Canyon underneath Interstate-215 to Knudsen Park and Holladay.

Schools, churches, and other community institutions create additional quasi-public private space for the greenways. For example, access agreements, with Bonneville First Ward, have extended the Miller Bird Refugee and Nature Park into Bonneville Glen along Red Butte Creek to create access on both sides of the park.

Neighborhood connections provide the most critical access points for our greenways. Networks of sidewalks and bike lanes from all stream-side communities should lead safely to the creek corridors. When private property prevents passage on the greenways, neighborhood byways can be used to circumvent, especially in the short-term, as access agreements or acquisition fill gaps in the system.

Signage and pavement markings can make connections easy for users. Paved trails, bridges, ramps, and overlooks along our greenways should be made ADA accessible. Non-paved trails should limit steep grades, steps, and mitigate barriers, such as excessive roots or large rocks.

Our creeks provide unique opportunities for swimming, wading, fishing, paddling, and floating, where feasible. Long-time residents of the Salt Lake Valley have fond memories of visiting swimming holes along our creeks to escape the summertime heat. Channelization, lack of access, and water quality concerns have diminished the safety and interest in these activities.

At the Little Confluence Trailhead in Taylorsville, where Little Cottonwood Creek meets the Jordan River, a boat ramp was constructed with a turnaround for vehicles pulling trailers. Paddlers can travel upstream on Little Cottonwood Creek until culverts, street crossings, or dams turn them around. Elsewhere at the site, a soft-surface trail winds through a restored cottonwood grove.

The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources is committed to creating more community fisheries; places where youth, families, and community members can walk, bike, or ride transit to catch a fish. For example, Fairmont Pond in Salt Lake City was dredged and turned into a community fishery in 2018. Rainbow trout were stocked and elevated boardwalks and walkways circle the pond. Several springs feeding the pond were uncovered and restored. New vegetation provides habitat and improves water quality. Additional community fisheries dot the Jordan River.

Maintenance is intricately linked to making greenways feel well cared for and safe. Regular maintenance, such as trash removal, weeding, landscaping, sweeping, and long-term repairs, are essential to a functional user experience. Greenways designed with intention provide community identity and pride.

Volunteers can assist municipalities with the upkeep of corridors, while developing long-term stewardship. Municipal-run volunteer programs fill maintenance gaps. Additionally, municipalities should consider financial support for community-based organizations who run robust volunteer programs. This can fill additional gaps in maintenance and upkeep of the greenways.

Conventional mitigation strategies for unsheltered homelessness often have the opposite effect. They increase dependency on parks for residency with displacement and loss of belongings. Housing can take longer than six months to secure [01]. A comprehensive strategy to address unsheltered homeless in our greenways is essentially to ensuring safety of all users—sheltered or not. Limiting clean-up of camps and longer posting times would mitigate loss of belongings. Helping individuals get access to services or having service providers respond to public complaints would address the underlying reasons of homelessness.

Efforts are underway to provide resources and facilities for unsheltered people. Practitioners along Red Butte Creek are exploring platforms that could serve as unsanctioned campgrounds. To provide bathrooms facilities for those experiencing homelessness, park managers are developing easily cleanable portable toilets housed within established framed outhouses. Showers can be an added amenity to support transitions into finding employment and housing.

Sources

[01] Neild, An exploration of unsheltered homelessness management on an urban riparian corridor (2018).

In a survey identifying strategies to mitigate impacts of dog parks on our streams, almost half of respondents agree with more enforcement and fines for not following off-leash regulations [01]. High dog use areas should be constructed away from buffer zones used to protect sensitive areas. Access should only be given at controlled points. Seasonal closures should be considered for nesting, breeding, and rearing of wildlife.

Regulations should be posted prominently at dog parks and on applicable websites. Phone numbers for enforcement should be posted prominently underneath regulations. Volunteer and community groups can assist with clean-up of dog parks and education around regulations. Finally, a fee forfeiture schedule, similar to parking tickets, could offer an alternative to criminal prosecution when taking enforcement action.

At Parleys Historic Nature Park, restoration efforts worked to mitigate the impacts of dogs and protect Parleys Creek. The riparian corridor was closed off except at designated access points. Educational signage and periodic enforcement further decreased negative impacts.

Sources

[01] Salt Lake City, Parks & Public Lands Needs Assessment (2019).

Multiple uses, abilities, and scales must be accommodated by our trails. Community feedback expressed a desire for different types of surfaces to accommodate multiple recreational uses. Soft-surface trails were prioritized over paved surfaces. This may be due to the current lack of these types of facilities along our creeks.

Regional trails are important to the active transportation network, connecting municipalities and major community and recreational nodes. They are ideally ten to 15 feet wide to allow for heavy two-way travel. The paved trail can be accompanied with a two to five foot soft-surface edge to allow for multiple uses. Concrete is most desirable because it is longest lasting and has low maintenance needs. All paved trails should be ADA accessible.

Soft-surface trails can spur off main paved trails to accommodate walkers, runners, and equestrians that desire a softer trail surface. Trails should be six to ten feet wide. Crushed stone is a popular surface as it is affordable, durable, ADA compliant, and compliments the surrounding environment. Edging along trails can hold crushed stone in place, so it does not erode into adjacent creeks. Soft-surface trails should be made ADA accessible wherever possible.

Unpaved trails for hiking and/or mountain biking are appropriate on uneven terrain that does not require ADA access. They should only be considered for our greenways after a paved trail has already been included. Widths can be one to three feet depending on use. Trails should be defined by compacting soil and using rocks or branches to line edges. Social trails should be eliminated by stick piles or rerouting to eliminate erosion and preserve habitat quality.

When trails pass through environmentally sensitive areas, vegetative buffers and spilt rail fencing prohibit access, screen wildlife, and protect habitat. In residential areas, fencing and vegetative screening protect privacy for adjacent properties.

Trailheads serve as primary access points. They should be visible, informative, and easily accessible. Signage should feature regional trail connectivity. Restrooms, waste disposal, and parking should be accommodated whenever possible.

Wayfinding signage breaks down barriers and improves access to the greenways and destinations. Directional signs, street crossings, and mile markers provide users with knowledge of where they are. Unified branding and graphics create a cohesive experience that transcends municipal boundaries. Emergency location markers, at regular lengths along the trail, help emergency services provide quick care. Regional trails maps should be incorporated into trailhead signage. Interpretive signage educates users about the benefits of our creeks and promotes stewardship of the greenways. They share the stories of significant places and people connected to the creeks throughout our history. All signs should be multi-lingual to promote inclusivity for all community members.

Safe and comfortable road crossings are critical to user experience. Crossings can be significant physical or perceived barriers for users. Whenever possible, grade-separated crossings are preferred. They minimize conflicts with traffic and provide a continuous pathway for recreation activities. Crossings of any type provide an opportunity to integrate art, placemaking, and signage.

Underpasses can be integrated into existing creek crossings beneath roads. Bridges easily accommodate trails underneath. Open-bottom culverts can be widened to feature both a trail and creek. In high flows, these culverts can flood out to provide additional capacity. Overpasses create grade-separated connectivity whenever underpasses are not feasible. However, they may require stairs or steep ramps that prohibit easy ADA accessibility and bike usage. At-grade crossings are the least desirable. If used, they should be safe and comfortable to preserve positive user experience. Pedestrian hybrid beacons, such as a HAWK beacon, should be used. They make for quick and comfortable crossings by stopping traffic and prioritizing users. Rapid flashing beacons can be used for less frequented crossings. However, they do not stop traffic and can be harder to see for vehicles. Crosswalks can feature painted artistic designs to slow vehicles. Crossing should also be combined with other street design elements, such as bump outs, lane narrowing, and mid-street refuges.

Our creeks can be culturally daylighted through art and placemaking. Cultural daylighting creates connectivity and brings awareness of our buried creeks to the collective consciousness. Temporary opportunities can be achieved through tactical urbanism—low-cost, short-term projects to catalyze long-term change.

Paint can challenge passersby to think about our buried creeks. For example, community members assisted in painting a stream over buried creeks in the Glendale neighborhood of Salt Lake City. A series of prompts, starting with “This would be a good spot for a creek,” guided users along the painted stream. For a more permanent solution, concrete could be used to represent the underground creeks. One idea is to pour concrete into a meandering channel design, coloring it a different shade to stand out. Prompts, depicting the creek names, could be pushed into the concrete. Thermoplastic markings could also be used for more intricate designs, such as logos, graphics, poetry, or narratives.

Murals along our greenways can highlight community connection to our hydrology. Stormdrain murals highlight stormwater infrastructure that empty into our creeks. Temporary or permanent installations are another way to draw attention to our creeks. They are a great opportunity for community engagement. For example, wooden fish—painted by community members—can be affixed to fences or other structures following the path of our creeks. A piece near the Three Creeks Confluence used three bridges to represent the underground waters of Red Butte, Emigration, and Parleys Creeks flowing on the west-side of Salt Lake City. Effort should be made to engage artists within the community the piece is placed.

Site features, such as benches or lighting, can be colored to stand out and depict the creek names, especially in areas with underground creeks. In the short-term, fountains can bring creek water to the surface to allow residents the opportunity to enjoy the water. Another idea is to put a pipe down into the culvert to listen to the running water underneath. Creative art and placemaking elements activate the greenways and creating engaging spaces that reflect nature and community.

Our communities are grappling with designing parks and open space for safety, while balancing goals for access, habitat, and water quality. Crime Prevention through Environmental Design is a recognized standard for approaching safety in the public realm. The principles include natural surveillance and space management. Greenways should aim for a constant stream of users at all times of the day to help with community surveillance. Night-time use, such as evening destinations along the trail, can go a long way towards deterring crime. Spaces should be attractive and well maintained. By engaging residents in the design of spaces, people feel more ownership over them. All design principles should be balanced with restoration goals and habitat value.

Comfortable and engaging experiences create memories and future stewards of our greenways. Amenities are critical in forming those experiences. They help users plan outings by knowing what will be available. Amenities should be prioritized based on a high to low need and high to low cost. High need amenities should be considered for each space along our greenways; low may be characterized by one or two per greenway or city. Consistent materials and color palettes build a cohesive branding for the greenways.

Priority for greenway amenities

Lighting can increase the sense of comfort during evenings, reduce crashes and falls due to uneven paving, and prevent collisions with other users and objects. However, it also increases light pollution and negatively impacts wildlife. To prevent impacts, lighting should be limited to key locations (parking lots, trailheads, plaza and gathering spaces, and other access points), trail crossings and along streets, on signage, and at bridges, underpasses, and overpasses. Dark sky compliant fixtures limit light pollution and buffer glare to adjacent residences. To address concerns, many facilities close after sundown, limiting their utility to trail users. With proper lighting at key locations, hours of operation can be extended. Lighting should be paired with educational efforts about bike lights, headlamps, and bright or reflective clothing for users.

If lighting is deemed necessary along a stretch of trail, low-level bollards can be used to cast just enough light. Lighting can be turned on mornings from 5AM to sunrise and evenings from sunset to 11PM to promote commuting and recreation. Lighting should be placed 100 feet apart, depending on the curves of the path. Solar and battery-powered options are the preferred option. They limit energy use and maintenance needs. In environmentally sensitive areas, lighting should not be installed.

Greenway implementation will require significant funding and alignment of resources. Sources are categorized by private, local, state, and federal and should be targeted based on the specific goals of each source. Greenways feature a number of different elements, including art and placemaking, playgrounds and play fields, park amenities, trails, and more. Creativity in funding sources for the different elements can improve effectiveness.

Private sources provide the greatest amount of flexibility and creativity in approach. Funds can be attained in countless ways. Many community foundations, nonprofits, and corporations provide grants for trails, open space, waterways, community development, and public health. Start with local community foundations and nonprofits, as well as corporations with headquarters nearby, then branch out. Land trusts, such as Utah Open Lands, provide an intermediary between cities and private landowners to negotiate acquisition of conservation easements or other strategies. To raise funds from community members, sections of trail or adjacent amenities can be sponsored, such as benches, trees, plazas, or buildings.

The most common source is at the municipal and county-level. Funds may be from a municipalities’ general fund or a specific department. They could be included in a capital improvement project budget. Or, a portion of sales tax set aside for greenways development.

Bonds can be used to raise significant funds. Like any campaign, you need strong community support, participation from elected officials, and hard work. Approved by voters in 2016, Salt Lake County successfully issued $90 million in bonds to build new parks, trails, and recreational facilities, as well as to renovate and improve existing facilities—many along our creeks.

Impact fees are a one-time charge imposed by municipalities to mitigate the impact on infrastructure caused by new development. They are a promising source to implement our greenways. For example, impact fees were a major funding source for the Three Creeks Confluence in Salt Lake City.

Tax-increment financing is a tool for municipalities to incentivize development in established areas. For example, tax increment dollars generate by developments within a buffer of our creeks could be collected and put towards implementation of the greenways. This would further increase property values and, thus, revenues for further efforts.

Potential local assistance ideas:

Funding for greenways from the State of Utah is administered through many state programs.

Potential state assistance ideas:

Sources from federal programs often have the highest revenue potential but can be burdensome, competitive applications. Some federal sources may require an environmental impact statement, which can complicate processes and increase expense.

Potential federal assistance ideas:

Policy will be crucial in achieving goals for the greenways. As creeks flow through numerous jurisdictions, recommendations represent an overall guiding document for policy considerations.

The first step for municipalities and land managers is to integrate the Seven Greenways Vision Plan into plans and projects already underway. Future general plans, parks and trails plan, economic and capital improvement plans, and ordinances should integrate these recommendations.

All municipalities along our creeks should adopt a riparian corridor ordinance. It is the next step towards implementing the vision and can be used to frame additional policy tools, such as development requirements or incentives, transfer of development rights, and acquisition.

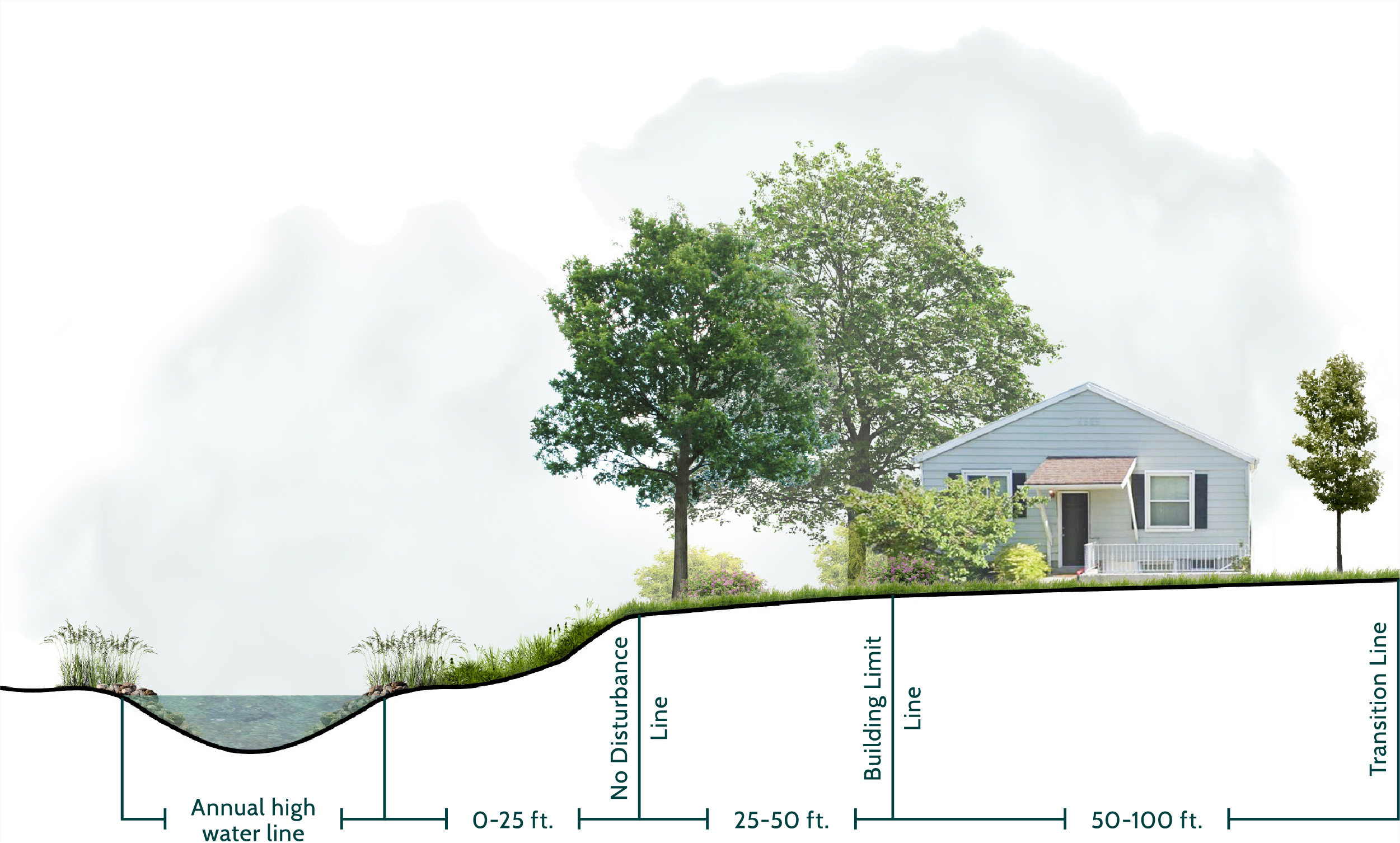

Ordinances should begin with a purpose statement that describes the benefits of protecting riparian habitats—improving water quality, providing habitat, mitigating flooding, enhancing recreational opportunities, and more. The applicability section states what is and isn’t subject to the ordinance standards, including geographic area, activities, and circumstances. A map further depicts where this overlay applies.

If permits are required to build in riparian areas, the ordinance should layout the type of permit and review process. It is common to require applicants do a resource inventory and impact analysis for the proposal. If impacts are anticipated, alternatives that avoid impacts should be included and weighed. If impacts are unavoidable, the proposal should be declined or, if deemed necessary, minimize and mitigate impacts.

The standards section should include the buffer zone standards. Salt Lake City’s Riparian Corridor Overlay Zoning District Ordinance divides the corridor into three zones: No Disturbance Area – 0 to 25 feet; Structure Limit Area – 25 to 50 feet; and Buffer Transition Area – 51 to 100 feet. Zones dictate activities allowed. Standards might address grading, structures, roads, vegetation protection and weed control, reduction of impervious surfaces, access and maintenance, land-use restrictions, landscaping, fencing, and flood control facilities. Additional permitting, such as the Utah Division of Water Rights’ Stream Alteration Permit, may be required.

The ordinance should allow for flexibility of unforeseen circumstances. This may be a process for landowners to modify requirements within defined parameters and subject to review. Enforcement of ordinance should be clear and include who is responsible for enforcement. Penalties and enforcement measures should be available for violations.

Creek-side properties are desirable areas to live, work, and play. Developments along our creeks represent our biggest opportunity to perpetuate the vision. When developers integrate goals, this provides amenities for their tenants, such as trail access, parks and open spaces, and access to nature, while improving their property values and bottom-line.

On properties within an established buffer of aboveground and belowground creeks, new developments should be required to uncover or restore creeks. If stream daylighting is not possible, the developer must show evidence. While the buffer is flexible, it could correspond to a riparian corridor ordinance, which typically extends out 100 feet from stream edge. Developers in underutilized lots adjacent to the greenways should be required to preserve a certain percentage of open space, cluster buildings (if applicable), and provide pathways and amenities adjacent to the stream. Public easements should be negotiated to ensure all community members benefit and have access.

Less ideally, incentives could be used to encourage developers to contribute to goals. A density bonus could be offered—greater square footage or number of units—to encourage stream restoration or daylighting, open space preservation, or trail creation. A planned unit development is a regulatory process that trades flexibility in the zoning code, such as building heights, density, or setbacks, for goals the municipality would like to achieve. Goals can align with those established in this vision. Developments go through an extra level of regulation, including a public engagement opportunity. This would be the ideal time to require developers study the possibility of stream restoration or daylighting. Funding or rebates for developers could be offered at the municipal or County-level to implement goals.

In Salt Lake City, Hidden Hollow is a serene, natural oasis within the bustle of the Sugar House neighborhood. In 1990, a group of elementary kids from Hawthorne Elementary cleaned up around Parleys Creek and successfully protected it through a conservation easement. Wilmington Flats and other dense urban apartment buildings have been constructed near this area, advertising “as a gateway to Hidden Hollow and Sugar House Park.”

A standardized certification process could be created for developments adjacent to our creeks within an established riparian corridor ordinance or overlay zone. Similar to certifications, such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED), the Creek-Friendly Development certification would follow a checklist of goals to achieve. The development is then awarded a level of certification (Bronze, Silver, Gold, etc.). This process would encourage developments achieve goals established by municipalities and this vision. The process could be managed by Salt Lake County, the municipalities, or a community organization, such as the Seven Canyons Trust.

Used to protect open space and environmentally sensitive areas, transfer of development rights is an innovative program to move development away from our creeks and floodplains to more suitable areas. In identified protection areas, such as those associated with a riparian corridor ordinance or overlay zone, development potential is sold to receiving areas in other identified areas of the municipality. The land is then protected in perpetuity through a conservation easement.

Acquiring strategic parcels along our creeks is a critical way to build out the greenways. First, parcels within an established buffer of our creeks—a riparian corridor ordinance or overlay can be used to dictate this buffer—should be inventoried for the highest priority acquisitions. A number of considerations can guide prioritization including zoning, existing land-use, structures on-site, size, cost, and more. Once properties are prioritized into a list, municipalities and partners can go top-down to inquire about acquisition.

Fee simple acquisitions are the simplest, yet most expensive. They transfer full ownership of the property including the title from the landowner to the buyer. Easements are one of the most widely used tools for conservation and public access. They can take many forms including utilities, roads, trails, or conservation. Conservation easements are best utilized for a property already in a natural condition, which the property owner is interested in protecting in perpetuity. Utility easements may be the most useful in facilitating stream daylighting. Landowners with buried streams may place a portion of their property into a utility easement. Once enough easements are obtained in a row stream daylighting becomes economically viable. Landowners receive compensation for these easements while obtaining valuable tax deductions.

Many water rights claims from mining operations and farmers predate the formation of cities along the Wasatch Front. This has led to intricate and complex exchange agreements. Cities get high-quality drinking water at the water treatment plants in exchange for rights to lower quality Utah Lake water through canals.

Big Cottonwood Creek is seasonally dewatered for four miles between the canyon mouth and Cottonwood Lane. From November to March, an estimated 50 percent of the creek runs dry within the scope area [01]. Between April and October, Utah Lake water is pumped into the creek to satisfy water rights. This has seriously degraded water quality and the riparian ecosystem. Little Cottonwood Creek has little to no flow in the scope area from July to March due to culinary and hydropower diversions. To supplement, Jordan River water is brought in, via a canal, at Fort Union Boulevard. This nine-mile stretch from canyon mouth to Fort Union is seriously impacted.

In 2020, the Utah State Legislature approved the Utah Water Banking Strategy, a three-year pilot program to study alternatives to water transfers. Utah is a “use-it-or-lose-it” state. If water rights are not put to beneficial use over a certain period, the right may be forfeited. Through the water banking program, rights holders can temporarily sell water rights without risk of losing this water permanently. This program could be critical to securing water for instream flows (such as in Big Cottonwood and Little Cottonwood Creeks to prevent seasonal dewatering), which improves water quality, recreation, and habitat.

Sources

[01] Salt Lake County, Stream Care Guide (2014).

The phenomenon of green gentrification can be an unfortunate impact of investments in our urban ecosystems, such as greenway creation, stream restoration, and daylighting. Efforts create desirable places to live, work, and play that attract wealthier and predominantly white populations. Without comprehensive strategies in place to prevent displacement, the residents these strategies are designed to benefit can be excluded.

Policy strategies at the city, county, or state-level are needed to prevent displacement due to gentrification. First, displacement should be tracked through migration demographics to understand how communities are changing. Projects that are inclusive and have broad benefits should be prioritize. In redevelopment projects adjacent to greenways, existing housing should be protected or efforts should ensure the same amount of housing stock, based on income level. Put simply, if replacing low-income housing, the same amount of low-income housing should be provided in the redevelopment. Additional affordable housing stock should be a critical part of any creek-side development. Rent subsidies, well-devised forms of rent control, and community land trusts to protect low-income and affordable housing are important city-wide tools to prevent displacement.

Special service districts are independent governmental entities separate from municipal and county governments. They can be used to meet a specific need, such as creek restoration, daylighting, and protection. They supplement existing services provided by municipal and county-level governments, extend across municipal boundaries, and can overcome financial barriers. However, they can also struggle with accountability and transparency. There are 400 local and special service districts operating in Utah.

Sources

[01] Utah Association of Special Districts, About Us (2021).

Collaboration, across governmental entities, nonprofits, community-based organizations, stakeholders, and residents, is essential to achieve this ambitious 100-year vision. This plan lays out general vision and strategies, but partnerships are critical in implementing projects. Stewardship of the greenways is fostered through increased awareness, enjoyment, and empowerment.

Greenways are a place for community to come together in connection with nature. While governmental entities are essential for the development and improvements of our creeks, community members play an important role in advocating for these places. Programs should bring together local organizations, stakeholders, and community leaders. Partnerships with educational institutions and universities, such as the University of Utah and Westminster College, can contribute to research efforts along the creek corridors.

For example, A forum for collaboration could be established between the eight stream-side municipalities, Salt Lake County, and the various stakeholders to advance implementation. This would bring together representatives and agencies with interests along the corridors and encourage them along the path towards implementation. Lessons learned and best practices could be shared to create more successful efforts.

Activation is one of the key ways to improve safety. Programs, events, and gatherings draw more users to green spaces and bring positive activity. Programming improves inclusion. Events can express community identity, promote shared values, and create a sense of place. They can showcase underrepresented voices and be a format for public discourse. Parks and open spaces provide residents with gathering space to celebrate diverse traditions.

The Range 2 River Relay explores the conditions of the Salt Lake Valley’s waterways from pristine headwaters to buried creeks and channelized canal to meandering river. Competitors bike, boat, and run from the Wasatch Range to the Jordan River. The event maps a drop of water through Salt Lake City’s hydrology from a snowflake in the Wasatch, through above and below ground stretches of City Creek, and into the Jordan River. It gets residents outdoors and active in family-friendly fun, improving public health and quality of life. Money is raised for efforts to create a greenway along City Creek, while building support for its future implementation.

This outreach teaches about our creek ecosystems, issues they face, and ways humans cause harm. Participants are empowered through teachings to take action, become stewards, and improve ecosystems around them. For example, the Seven Canyons Trust’s Seven Creeks | Walk Series is a program to observe and share stories, insights, and visions to better manage, restore, and love our creeks. Participants engage in on-the-ground actions to build community connection and improve their local ecosystems. After programming, 90 percent of participants reported they understood why creeks are important and 90 percent understood the issues they face. Approximately, 64 percent felt they made a difference during programming and 65 wanted to participate in stewardship actions again [01].

Creeks function as living laboratories for nearby schools and institutions. For example, Westminster College students in the Environmental Studies program survey the hydrology of Emigration Creek, through the Seven Creeks | Walk Series. Students follow the creek as it goes below ground outside of campus, tracing it underneath houses, parking lots, and roads, to Liberty Park. They learn about opportunities to uncover the creek and actions they can take to improve its health. Students take this knowledge back to campus and use it to frame water quality testing on the creek and further education on its hydrology.

Service-oriented volunteer efforts can ground environmental education teaching with on-the-ground, meaningful activity. Efforts can directly implement goals in this vision, such as habitat restoration, landscaping, and hardscaping. Partnerships with corporations, places of worship, clubs, and community-based organizations provide a valuable source of labor for efforts.

Sources

[01] Seven Canyons Trust, Seven Creeks | Walk Series survey data (2021).